How all the mortgage debt we've racked up will see an OCR hike have a particularly large cooling effect on the economy

By Jenée Tibshraeny

The first Official Cash Rate (OCR) hike in seven years is expected to have a particularly large cooling effect on the economy.

ANZ chief economist and Sharon Zollner and Triple T Consulting managing director Sean Keane expect the economy to be more sensitive to an OCR hike - which markets are pricing in for November - than a cut.

Accordingly, Keane believes the Reserve Bank (RBNZ) won’t need to do a lot (make too many hikes) to meet its inflation and employment targets.

Zollner expects it to lift the OCR in steady steps from 0.25% to 1.75% by February 2023.

The last time the OCR was increased was in 2014, when four 25-basis point increases took it to 3.50%.

First hike the sharpest

In general terms, Zollner said the first hike is always the sharpest, just as the first cut is the deepest.

She said there was a risk financial markets could take a 25-basis point OCR hike and run with it, tightening monetary conditions more than the RBNZ might be comfortable with.

Keane noted that after seven years of money becoming cheaper, there is some uncertainty around how people will respond to having to get their heads around money becoming more expensive.

However, there are some specifics in the current environment that mean the RBNZ will get traction when it hikes interest rates.

Bulk of mortgage holders will be affected soon

Firstly, it’s hard to look past the big increase in mortgage debt that has accompanied years of interest rate cuts.

The value of bank mortgage debt has increased by 11% over the past year to $311 billion, meaning New Zealand’s mortgage debt is now worth almost the same as the entire economy, or annual gross domestic product ($325 billion).

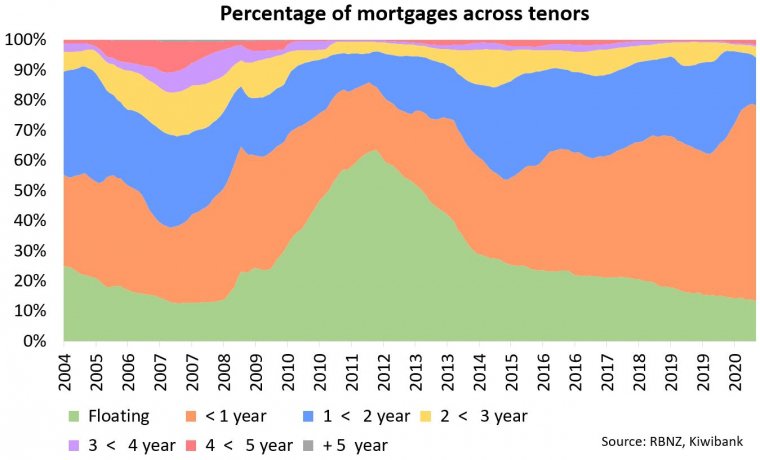

As interest.co.nz reported in May, the bulk of this debt is due to rollover within the next year, so the effect of higher rates will be felt by a number of people fairly soon.

According to Kiwibank chief economist Jarrod Kerr, 60% of mortgages are either floating or up for refixing in the next three to six months. Meanwhile 80% of the country’s mortgage book will refix in the next six to 12 months.

“That’s an enormous amount of fixing flow into a tightening cycle,” Kerr said.

Zollner also made the point that while mortgage rates may only go up by couple of percentage points, the increase is proportionally larger in a low interest rate environment.

For example, a mortgage rate hike from 2% to 4% is a 100% increase, while a rise from 6% to 8% is only a 33% increase.

Interest rate hikes to coincide with tax hikes

Keane noted that on top of people getting their heads around money becoming more expensive, the government’s tax changes will soon start biting.

These include the new top income rate of 39% (which took effect in April), the removal of interest deductibility (which is being phased in over four years) and the extension of the bright-line test from five to 10 years.

Keane believed the combination of these policy changes will keep the RBNZ’s tightening cycle short.

Indeed, with house prices up around 30% over the year, Zollner said the RBNZ would need to feel its way genteelly when tightening monetary policy.

However, she said the later it starts, the more it will need to scramble to deal with an over-heated economy.

She said the economy no longer needs higher demand. Rather, it needs more resilience

RBNZ research done pre-Covid reaches different conclusion

With the RBNZ due to publish a Monetary Policy Review next Wednesday, it didn’t comment on whether it believed the economy would be more sensitive to an OCR hike than a cut in the current environment.

However, research it did in 2019 (before it started using “unconventional” tools like quantitative easing) concluded the impact OCR changes had had on consumer inflation and economic growth had been stable since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

‘Indebted demand’ theory

Keane had a different view, arguing that economic responses to central bank policy adjustments have changed in recent years.

He pointed to the theory of indebted demand, explaining that as borrowing becomes cheaper, people take out more debt.

The cost of servicing that debt lowers spending, consumption and thus economic growth, prompting central banks to lower interest rates again. So, the stimulus/debt cycle repeats.

Eventually, all the monetary and fiscal stimulus halts the downward spiral, and central banks can start hiking rates again.

However, Keane said because every 25-basis point OCR hike will affect a larger pool of existing debt, hikes will bite, and the RBNZ won’t need to lift the OCR by very much to achieve its inflation and employment objectives.

This story was originally published on Interest.co.nz and has been republished here with permission.